I can’t help but want to talk about perhaps too many things in this post, as I know many of us are still reeling after last week. Perhaps shocked and blindsided, perhaps proven right in the worst way possible, perhaps teetering just above despair. Anyone celebrating is invited to leave at this point. Anyone lashing out, lighting fires, throwing blame at those more vulnerable than themselves, screeching “I told you so” as they rub salt into others’ open wounds, is invited to seek therapy.

It feels very strange and not a little delusional to be talking about my book at a time like this. Not that it doesn’t feel strange to talk about the future at all, given how little we can say for certain about it, other than that things look bleak. They certainly look bleak if, like me, you are a queer author who writes queer books. As I discussed at length in my previous blog post, we could easily be entering a dark age in terms of art and literature, an age in which books like mine will become hotly contested objects. But it’s one thing to worry about whether or not your book might still be legal in your home country a year from now, quite another to worry whether you, as a human being, will also be legal: your marriage, your passport, your family, your friends, your livelihood, your joy, your resistance, your thoughts, your dreams.

However, as a number of other queer authors have also pointed out, there’s no sense whatsoever in backing down before the fight has even truly begun. We are already tired, especially those of us who have been targeted before, but I hope we are far from giving up. Now is a time for those of us who can afford to be loud to scream with all our might.

Knowing my history as a queer person is a double-edged sword, because I’ve seen my community in its darkest hour, but I’ve also seen us emerge from that darkness, again and again. Whatever is coming, we have every right to feel dread in the pits of our stomachs, but also every reason to believe we will find ways to survive it. As Marlowe says in Lightborne, “to live is a form of vengeance, when so many have sought to destroy you.”

As long as humanity lives, we live. I’m sure it drives those who hate us crazy.

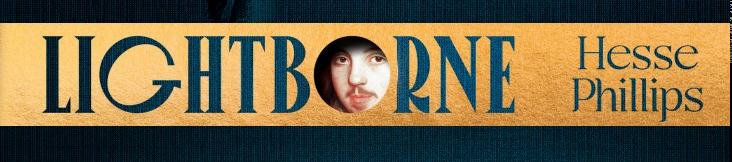

All that said, I’m extremely lucky to have exciting things to look forward to in 2025, among them the paperback launch of Lightborne in the UK. Come what may, in March there will be a whole new edition of the book out in the world, with a stunning new cover to rival the old one.

And now, without further ado:

We still have the beautiful gold accents that gave the original cover such a bold presence on the shelf, but now with a much darker, moodier atmosphere, and even a subtle appearance from Kit Marlowe himself. I chose this design among several options – it wasn’t easy, as they were all impressive – but I loved this one for that rich blue tapestry background, and the vintage feel of the design.

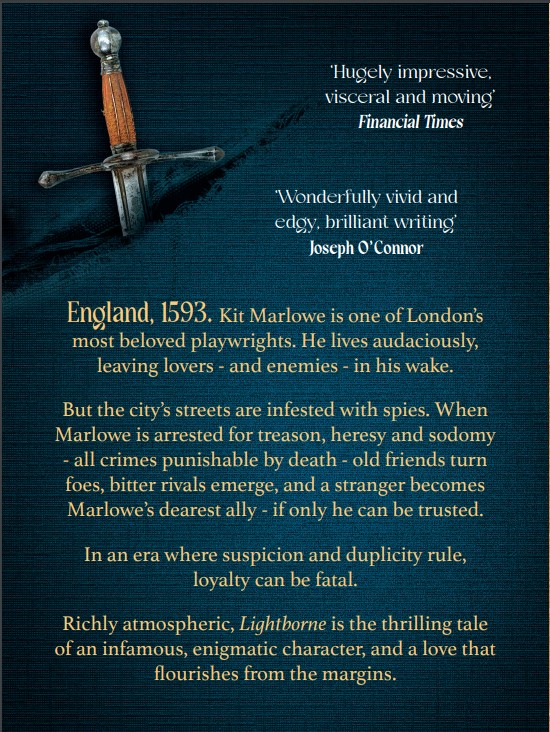

The back cover, I should add, is equally gorgeous:

Those who have read the book already will surely recognize Frizer’s knife peeking out! I fought for that knife, I will say, and I’m so glad I did. Authors – this is me advising you to fight for things you want on the cover. You might not get them, but you’ll have no regrets.

I’m beyond excited to see the paperback in its full glory, as I hope readers will be as well. Whatever dangers are barreling down at us from the future, I hope we’re able to find reasons to stay excited and engaged. After all, the world desperately needs that from us. Our anger and outrage is necessary, but so is our hope, our creativity, our joy.

It might mean the difference between simply getting through whatever comes next, and doing the work that desperately needs to be done: of building a better world than the one we started with.