Content Warning: this post discusses historical cases of violence against women, including r*pe.

Hi. This is me poking my head out of my writing cave, wanting to talk about a work-in-progress for a minute – perhaps an incredibly foolhardy thing to do, because after all, there are no guarantees that any work-in-progress will ever come to aught. It’s Schrodinger’s book, as it stands. But with any luck – and a lot more work – perhaps it will one day step out of the box, alive.

For now, at least, I’m calling it The Devils of Denham Manor.

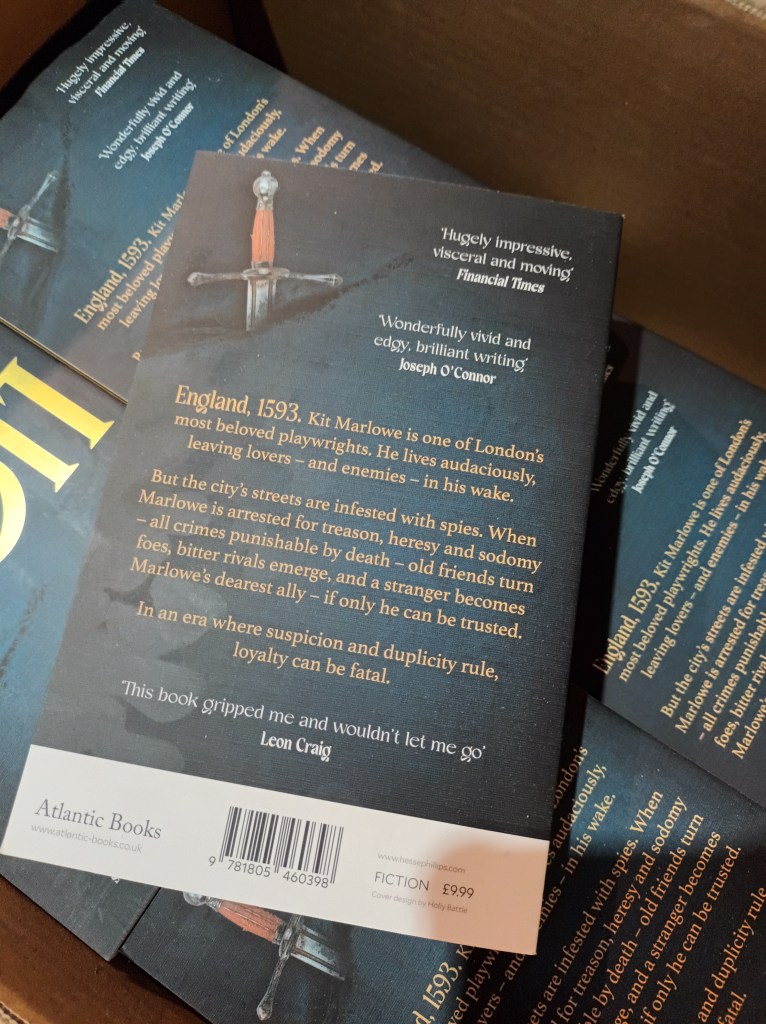

Like my first book, Lightborne, it is based on a true story of a crime which has gone unresolved for centuries. The case was well-documented in its time, though nearly forgotten today. At the heart of “The Devils” lies a sex scandal, which unfolded at the remote country estate of Denham Manor over the winter of 1585-6. For some eight months, an underground group of Catholic priests forced three teenaged girls to feign demonic possession before paying audiences of Catholic sympathizers and the morbidly curious. The priests’ stated purpose, in a nutshell, was to “prove the truth of” their faith through demonstrations of the supernatural powers it bestowed on them. Powers such as the ability to exorcise of “all the devils of hell.” They also undoubtedly made a lot of money.

By the early 17th century, the Denham “demoniacs”, and the names of their supposed resident demons, were so infamous that Shakespeare quite cheekily dropped them a reference in a famous scene of King Lear:

Bless thee, good man’s son, from

the foul fiend! Five fiends have been in poor Tom at once: of

lust, as Obidicut; Hobbididence, prince of dumbness; Mahu, of

stealing; Modo, of murder; Flibbertigibbet, of mopping and

mowing, who since possesses chambermaids and waiting women.1

Just two years earlier, a book recording the women’s ordeal at Denham Manor had been published to enormous success: an instant bestseller, you could say. Such was due in part to the book’s sensationalist and often comic tone, lingering on the salacious details of three girls held captive, “used and abused,” by a group of older men. If the women did not become household names, their “demons” certainly did: Modo, Maho, Flibbertigibbet, Hobbidicut, Hobberdidance.

As so often happens in the aftermath of a scandal, many contemporaries – evidently, Shakespeare among them – sought to turn the whole episode into a joke, and the women into collaborators in their own abuse. Some of the events that went on at Denham were indeed ridiculous, and the exorcisms themselves sometimes had the audience in stitches rather than cold sweats. There were dirty jokes, grotesque dances, songs, and ribald jabs at the Protestant Queen Elizabeth and her ministers. But reading the testimonies of the victims paints a very different and far darker picture.

The youngest victim in the Denham case, a chambermaid called Sarah Williams, was only fourteen or fifteen when her exorcisms began. As an adult reflecting on her experiences, Sarah claimed that her captors frequently enhanced her performances through the use of intoxicants, plus physical and psychological torture. While Sarah herself never explicitly alleged sexual abuse – for, of course, the legal language to make such an accusation did not exist at the time – her recollections of the “exorcisms” to which she was, remember, publicly subjected, quite clearly describe acts of sadism, sexual aggression, and even rape.

I want to spare you the details. Broadly speaking, Sarah’s exorcisms involved a range of bodily violations, from the forced ingestion of “potions” and inhalation of “fumes,” to the “Laying-on of Hands,” in which a priest fondles, pinches, or even wounds the possessed, supposedly in order to “chase” the devil through her body. Most horrifically, Sarah alleged that the priests of Denham would often squirt caustic liquids or insert objects – including human bones, or relics – into “her priviest part.”2

Sarah’s story may be 400 years old, but it feels like a wound that might easily have been opened only yesterday. With the Epstein Files still dominating the news cycle, not to mention online discourse; the mass-rape Pelicot Case still unresolved; the egregious institutional failures at the heart of the UK “grooming gangs” scandal leaving survivors feeling abandoned; the fact that a convicted sexual abuser now holds one of the highest positions of power on the planet… The list goes on. If 2017 was the Year of MeToo, then you might rightly call 2025 the Year of the Rapist.

One wonders whether much really has changed since Sarah was abused before a crowd of willing (and paying) spectators in 1586, or since she described her abuse to a panel of lawyers and churchmen in 1603. Then as now, rape largely went unreported and unpunished. Although Elizabethan legal experts often classified rape as second only to murder, earlier laws determined rape to be more a matter of property loss for a woman’s male relatives than a serious offence against the body of a woman.3 (I don’t say “bodily autonomy,” because the concept did not exist, less so when pertaining to women and children.) The few rape cases that did make it to court rarely resulted in convictions against the rapist, and even occasionally resulted in the accuser being penalized for slander, adultery, or indeed “fornication.”

Moreover, according to medieval statutes dating back to the 13th century, a woman who had been raped was obligated to make a spectacle of her own anguish if she had any intention of seeking justice:

She ought to go straight away and with Hue and Cry complaine to the good men of the next towne, shewing her wrong, her garments torne, and any effusion of blood[.]4

In other words, she had to present herself as “the perfect victim” – an all too familiar scenario in today’s discourse. She had to object loudly and early, be visibly distraught, disheveled, and damaged; she had to show contrition for “her part” in the crime and “seek for Everlasting Night,” as one poet put it.5 She could, by no means, become pregnant, as pregnancy was then believed to only result from consensual sex. Her life and her world came to a screeching halt.

Perhaps this is why accusations of rape were so rare, amounting to just 274 in the 142-year period from 1558 to 1700. Out of those 274 cases, a mere 45 resulted in convictions.6 For comparison, it is estimated that some 900,000 people over 16 were sexually assaulted in England and Wales in 2024. From June 2023 to June 2024, 69,184 rapes were reported to UK police, of which a mere 49% resulted in a conviction. That’s nearly 70,000 prosecutions in one year, versus just 274 over a period of more than a century.

But Sarah Williams and her fellow “devil-girls” of Denham Manor were not among those 274 litigants. For the Elizabethan authorities, rape ranked low amongst the crimes of their abusers, several of whom were tried and executed for attempted regicide. In fact, after the exorcists’ ring was broken up, Sarah, as well as her sister Frideswood “Fid” Williams and another girl, Anne Smith, all endured months in prison for their presumed complicity in treason. Upon release, all three spent the next seventeen years of their lives either laying low or in and out of trouble with the law, begging for audiences with religious and political figures or avoiding them like the plague, torn between a desire for safety and a need for justice, a need to be heard. To be believed.

I’m sure this is why, when I stumbled upon Sarah’s story while researching something unrelated, I felt immediately compelled to tell it.

Unusually for her day, Sarah’s record of abuse survives, mainly because the powers-that-be found it politically expedient to sensationalize it. By 1602, when Sarah, Fid, and Anne received their summons, Queen Elizabeth’s health was failing, and the heir apparent to the throne, James VI of Scotland, had shown leniency towards Catholics in the past. For those who hoped England would remain Protestant after the queen’s death, a wild story about three innocent girls tortured and raped by a gang of Catholic priests was everything they could have hoped for: a way to push sanguine English Catholics back into the shadows, and make certain the incoming James would know his place.

For that reason, some scholars have discredited the women’s testimonies over the centuries, proclaiming them to be only another clever piece of anti-Catholic Elizabethan propaganda.7 But details of the exorcisms had been reported in earlier depositions given by both Sarah and her sister. Who are we to believe? Men for whom such testimonies, if proven true, would be disastrous, or women for whom the giving of that testimony was itself a disaster – a sacrifice of their privacy, security, and peace?

For over 400 years, Sarah’s story has existed only as her inquisitors saw fit to record it, not in her voice, but in the third-person. The tragedy in this is that Sarah’s abusers at Denham had also denied her a voice, claiming that any sound she uttered or move she made came not from her, but from the devil inside her. In one instance, as Sarah implored one of the priests to stop the exorcisms, he

cast his head aside, and looking fully upon her face under her hat, said, ‘What, is this Sarah or the devil that speaks these words? No, no, it is not Sarah, but the devil.’ And then [Sarah], perceiving that she could have no relief at his hands, fell a-weeping, which weeping also he said was the weeping of the evil spirit.8

This is another form of rape, I think, of the kind that leaves no marks. But then, every rape of the body is also a rape of the mind, the soul. It is a form of possession: the demon that takes up residence, and robs the host of all credibility, empathy, and humanity. Telling the story is a flawed form of exorcism, as anyone who’s ever had to tell such a story knows: incomplete and arguably performative in its own way, so desperate to be witnessed, to be believed. But it’s something.

I hope I can do Sarah, Fid, and Anne some justice, for whatever that’s worth.

- William Shakespeare, King Lear, IV:1, 2312-9. ↩︎

- Descriptions of Sarah’s torture can be found in Samuel Harsnett, A Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures, 1603, pp. 78, 110, 120, 175, 181-3, 185. ↩︎

- Julia Rudolph, “Rape and Resistance: Women and Consent in Seventeenth-Century English Legal and Political Thought.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, 2000, pp. 157–84. ↩︎

- Nicholas Brady, The Lawes Resolution of Women’s Rights, 1632, p. 392, quoted in Bashar, p. 35. ↩︎

- Nicholas Brady, The Rape, Or The Innocent Imposters, 1692. ↩︎

- Bashar, p. 35. ↩︎

- See F.W. Brownlow, Shakespeare, Harsnett and the Devils of Denham Manor, University of Delaware Press, 1993. ↩︎

- Modern English transcription by Kathleen R. Sands, in Demonic Possession in Elizabethan England, Praeger Press, 2004, p. 104. ↩︎